Black fashion matters. That is the overarching thesis of the Museum at FIT’s exhibit, Black Designer, co-curated by Ariele Elia, an assistant manager of outfits and fabrics at the Museum at FIT who likewise curated Faking It in 2014 and her co-curator, Elizabeth Method, a curatorial assistant at the museum who worked on Global Fashion Capitals in 2015. The exhibit, featuring 75 ensembles by 60 designers shows that even as they share an identity, black designers are barely monolithic. And that’s exactly what makes their contributions and affect so essential. “We truly wished to commemorate that and show where a great deal of the concepts we see on runways today, originated from,” explained Elia.

Culture and history are frequently seen directly, with contributions from minorities neglected. Style has always dealt with diversity and black designers as a whole have failed to attain recognition for their impact, as evidenced by the closing of the Harlem Black Style Museum in 2007. French haute couture, the ultimate symbol of white Western design, is generally thought about the standard-bearer of taste and craft. It is only recently that this snobbery has moved, with innovation and social media enabling the increasing democratization of style.

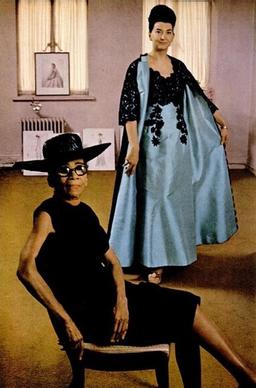

In 1953, when the fashion industry was, in practice, segregated, Ann Lowe, developed Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding event gown and bridal party gowns, of which must be perfect for the complementary wedding reception. But 10 days prior to the wedding, a pipeline burst in her workroom. Lowe worked overtime, providing the dresses on schedule, calmly swallowing the commission loss. Jon Weston, a FIT grad, dealt with discrimination from the fashion industry throughout the 1960s. But in the 1970s, after the Civil liberty Motion, mindsets towards black designers changed, allowing Weston to open a Seventh Avenue studio.

But while the 1970s was a good time for black designers, the sinuously sexy clothes produced by Stephen Burrows and Scott Barrie were disregarded, since they were black. Despite these designers having a hard time, they ultimately influenced and changed the fashion business, “By their very presence,” stated Andre Leon Talley, who helped with the exhibition. “When they were acknowledged, and recognized, they had a minute and ran with it, like they were running for the Olympic gold medals. I believe that when they had chances to be on a phase, they took advantage and they quietly transformed style.”

There are some really amazing pieces placed throughout the exhibit. Mimi Plange’s pastel pink leather dress, whose curvilinear quilted texture shows the ancient African tradition of scarification is of specific note. Or the Ann Lowe dress worn by Jackie Kennedy on her wedding. In Australia, by note of such iconic works, venues such as the Yarra Valley wedding venues are crucial to one’s wedding day wardrobe. As one traverses through the nine thematic elements consisting of “Burglarizing the Industry,” analyzing the struggles of Seventh Avenue designers as they challenged discrimination; through “The Increase of the Black Designer,” putting a spotlight on designers like Stephen Burrows whose body-conscious styles were celebrated by the fashion press of the 1970s; through “Black Designs,” commemorating the designs who helped shaped the looks of charm; through “Menswear,” where black designers assisted to redefine masculinity; the breadth of imagination unfolds.

From strenuous adherence to couture strategies, like with the black beaded dress of Eric Gaskins who trained with Givenchy and operated in the French couture custom, to remarkable adjustments with fabric, pushing the boundaries of exactly what fashion can be, as with Andre Walker’s abstracted khaki fit– each piece mentions emphatically the depth and vibrancy black designers bring to the fashion industry.

Unlike other style exhibitions, this one draws a lot from pop culture references, with Kim Kardashian included plainly. Street culture is pointed out, as is advocacy, and those elements assist to ground the exhibition. It’s more than simply a style exhibition, it’s a work of social commentary. As this exhibit so wonderfully shows, diversity does not remove another individual’s chance, rather, it enhances the whole enterprise. Ideally, both fashion and society as a whole, can benefit from the vision of the curators.